Charles Thomas-Stanford: A river of Norway (1903)

Charles Thomas-Stanford var ein av dei mange engelskmennene som rundt århundreskiftet 1900 kom til Noreg for å fiska laks. I 1903 skreiv han boka A River in Norway. Elva var Gaula og boka kom året etter på norsk. Eit kapittel handlar om laksetrappa i Osfossen som iraren William T. Potts bygde i 1869. Trappa er den eldste kulpetrappa i landet.

"Ah! Who can tell how hard it is to climb?"

(BEATTIE, The Minstrel).

Planned and built by an Irishman

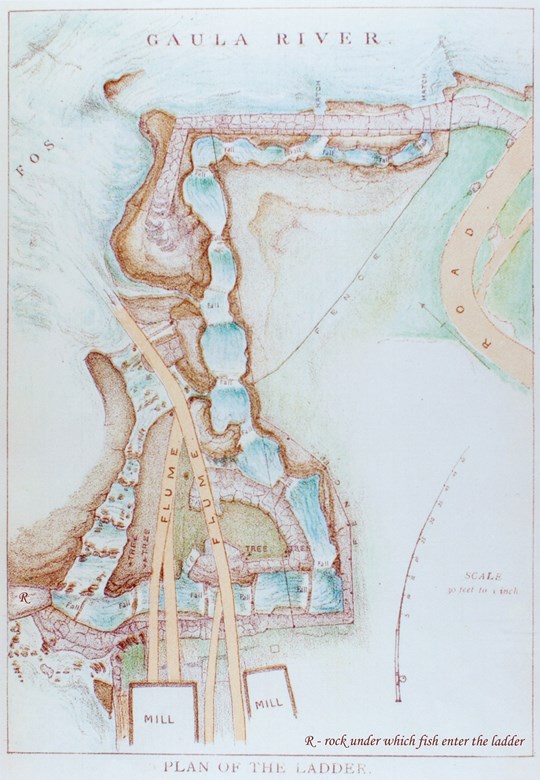

The ladder which gives fish access to the river above the great Fos was constructed about thirty years ago by an Irish gentleman, who owned the property of Osen, extending for about two miles upwards from the mouth of the river on the left bank, and made contracts with the other proprietors interested, which gave him the fishing rights for a long term of years. It was probably the most important fish-pass in existence at that period, though it has since been surpassed by the great Vefsen ladder, and possibly by others.

It has in every way been most successful. Not only has it created a salmon fishing ten or twelve miles in length, but by opening up excellent spawning grounds it has vastly improved the race of fish which had previously frequented the water below the great Fos. This process, if one may believe the evidence of the oldest inhabitant, is still continuing.

The construction

The obstacle to be circumvented is an almost sheer fall of fifty or fifty-five feet in height. To mitigate the steppness of the ascent the ladder takes a zig-zag course. The entrance to it is directly from a natural shelf at the bottom of the Fos, the water on which is at high-tide level with the pool below.

There are in all sixteen steps, the leaps from one to the other varying from three to four feet in height. A few are rather rapids, up which fish easily swim, than leaps. The little pools are of different size and shape; for the most part the water in them is rough and foaming, but some have more or less quiet backwaters in which fish may rest awhile. At the top is a strongly-built wall running upwards from the head of the fall and high enough to keep the river at highest flood out of thee ladder; and through this fish-pass by one or other of two hatches, used respectively in big or small water, into the quiet and deep pool above.

The greater part of the ladder is blasted out of the rock, the steps being built up with stonework and baulks of timber; the whole presenting a very natural appearance, a point of some importance. Certainly fish do not seem to have any trouble in discovering it, or to be afraid of the confined stream in which they find themselves; and we have occasionally killed fresh-run fish in the river above, which must have come straight through from the fjord with very little delay.

From early June

In most years single fish begin to run up the ladder early in June, but there is as a rule no great run until towards the end of the month, and sometimes it does not occur until July. Such a run generally takes place when the river is rising after rain, the temperature of the water being also higher. But this rule is not invariable. I have not yet been able to discover any law in obedience to which thousands of fish suddenly take it into their heads to run up.

Below is a list extracted from my Diary of the earliest dates on which fish have been seen in the ladder, and those on which there was any considerable run of fish:

1898. (No record of the first fish seen, but fish were certainly in the ladder before June 14. )

1898. July 5. - A large number going up.

1899. June 11. - A fish.

1899. July 2. - A great many fish running. The run continued for two or three weeks.

1900. June 13. - A fish.

1900. June 15-19. - Several fish.

1900. July 1. - Many fish.

1900. July 14. - Ladder crowded with fish after heavy rain.

1901. June 5. - A fish.

1901. June 23. - Numerous fish after continued rain.

1902. June 18. - A large fish.

1902. June 23. - Several fish.

This season there was never any quantity of fish running, and it was reported to me that in August and September there were very few in the river.

1903. June 23. - Some fish.

1903. July 4. - A few fish.

1903. July 16. - Ladder very full of fish - a big run, which lasted without intermission for a fortnight.

A mystery

This year, 1903, in pursuance of its character of a very late and entirely abnormal year, scarcely a fish was to be seen in the ladder until the middle of July. On the 16th the run began. There was no apparent cause. The weather had been cold and the river was falling slighly every day. Certainly the day itself was fine and warmer, but the river was not yet affected. Yet suddenly it was alive with fish.

I the course of the next few days thousands must have gone up. Where they all came from was a mystery. Very few had been showing in the pools below, and sport though good occasionally had been intermittent. I cannot avoid the conclusion that numbers of fish which had come from the fjord in the previous six weeks had dropped back to it again, until the atmospheric change - or whatever it was - occurred, which caused them to make for the upper waters.

The run continued without intermission un til we left at the end of July, but latterly was composed chiefly of grilse, which were coming in from the fjord in great numbers at the time. They were accompanied as usual by a few salmon; on the 22nd we killed two, 13 lb. And 24 lb., with sea-lice. The fine weather which had set in on July 16 lasted until the end of the month. The river was daily higher, and the temperature of the water rose from 50 (degrees) [Fahrenheit] to 56 (degrees). It looks as if the salmon when they commenced running on the 16th knew the conditions which were coming.

Amazing

When fish are running it is a never-ending source of amusement to us to watch them. You may stand by the side of one of the steps with a crowd of salmon within a few feet of you, many of them half out of the foaming water. Sometimes a fish will jump one of the little falls, and, merely skimming the pool above, will take the next fall "in his stride". And a glorious sight it is to see a 20-pounder making so light of the obstacles.

Other fish seem to have a dislike to jumping, and will swin up the falls, with much twisting of bodies and whisking of tails; a far more toilsome means of ascending, one would suppose. Others seem to have no eye for their work, and will jump short or crooked, and fall back over and over again. Most of the pools are so built that it is difficult for a fish to jump right out on to the rocks, and I have only known one to do so, and be killed.

At the top

Very interesting too is it to stand on the wall at the top of the ladder and see fish come through the hatch into the river above. After the turmoil of the little pools it must be a startling change to enter the spacious smooth running river; and they usually appear to pause a moment and to contemplate the situation. Then they sail away majestically into the depths, and unless we chance to meet them higher up, are no more seen.

No poaching

It is fortunate that the inhabitants here have no very highly developed taste for poaching. It would be easy to take hundreds of fish out of the ladder in a single night. In some countries, which shall be nameless, it would require at least four men to guard it, and they would have to be heavily armed. I am thankful to say that I have never had the slightest cause for suspecting any unlawful proceedings on it here.

Accounts of Salmon ladders

The best account of salmon ladders in general which I have found in any work on angling is contained in "Fishing in American Waters", by Genio C. Scott (New York, 1869), an interesting and amusing book. After remarking on the necessity of admitting salmon to the upper and shallow portions of rivers, if the race is to be preserved, the author proceeds to discuss the conditions under which salmon can leap up a fall. The main requisite is a sufficiently deep pool below, in which to attain, by means of a run, enough impetus and velocity. The absence of this sometimes makes a mill-dam only three or four feet in height impssable.

The provision of suffcient water to take off on for each leap is really the main factor in the success of a ladder; and it has been well carried out in our ladder here. Mr. Scott gives some particulars and illustrations of different ladders in America and elsewhere. Perhaps the most interesting is the well-known salmon pass at Ballisodare, in the west of Ireland.

An article entitled "Salmon Passes", by A. F. Bruce, A.M.I.C.E., may be found in the Transactions of the Civil and Mechanical Engineers Society, 1887-1888, and should be consulted by any one anxious to ascertain the conditions and cost of a successful ladder.

A lasting memorial

If "whoever could make two ears of corn, or two blades of grass, to grow upon a spot of ground where only one grew before" would deserve well of mankind, then no less meritorious is the man who has peopled a useless river with the noble race of salmon. To the enterprise and ingenuity of the Irishman who planned and built it, this ladder of the river Gaula, in Norway, is a lasting memorial.