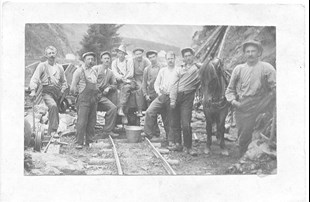

Village people became railway workers

The railway construction in Flåm led to an emergence of a new industrial group. Quite a few people from the area were employed, either as transport workers or as railway workers. Some of the workers found their wives in the valley and settled down there. At many places both father and son worked at the construction sites. At first the workforce counted about 120 men. During the hard economic times after the First World War, fewer workers were employed, which meant that the work schedule could not be kept. The number of workers increased to 280 in 1937. In the war years an average of 75 persons worked at the sites. In addition to those who were permanently employed at the construction sites, many people were working with various transport jobs, and cooks and others who carried out various services were paid by the work teams.

Workers' barracks

As there were few farms up along the valley, barracks had to be built to accommodate the workers. There were eight barracks in all; three at Myrdal, one at Kårdal, one at Berekvam and one at Høga in addition to two at Flatedalen between Høga and Flåm. The latter two were built as family barracks. In each barrack, 16 men shared four rooms. Some of those who had families lived in private quarters. The office workers lived in their own houses at Flåm and Myrdal. At Myrdal a complete local community grew up with a general store, sub-post office, long-distance telephone exchange and a school (from 1899 to 1982) which even had a swimming pool. At Berekvam there was also a school, sub-post office and general store, in addition to a small café at the post station. There the horses had to rest before starting on the final heavy leg up to Myrdal.

Life as a construction worker

It was heavy going indeed. Most people worked all day long, and most of the work was carried out by hand. They worked on contract and the piece rate was 1.60 to 1.70 kroner per hour. In addition, there was a special family allocation of five øre per person supported in the worker's household. This arrangement lasted until 1929. From 1930, a special mountain supplement was introduced - 10 øre per hour - on the upper section of the Flåm Railway from Myrdal down to the upper entrance to the Nåli tunnel. The work team had to pay for cook and blacksmith. The cook was paid 18-25 øre per day from each worker. The blacksmith sharpened the drills and repaired the tools that the work team had to provide themselves. The work team also paid for the dynamite they used. At first there were three labour unions at the construction sites. With improved communication, these three were united into one.

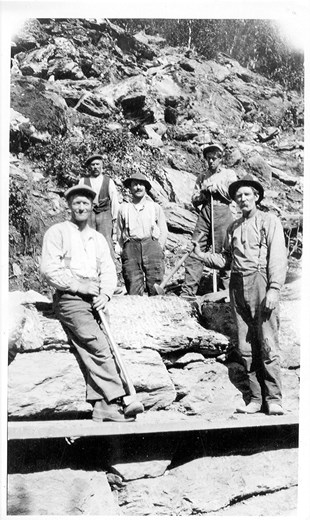

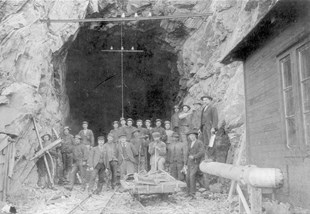

Tunnel construction

Because of the danger of avalanches and the difficult terrain, the Flåm Railway has 20 tunnels in all, with a total length of 5692.6 metres. This is close to one third of the whole distance. The longest tunnel measures 1341.5 metres. In addition, a number of "snow roofs" were built between Myrdal and Bakli. All tunnels, with the exception of Nåli and Vatnahalsen were drilled by hand. The tunnel work was far from safe. One man lost an arm and two men died in 1925 and 1938. Those who carried out the drilling were particularly exposed to drilling dust, and many workers probably died of silicosis or were afflicted with other diseases for the rest of their lives. In 1937, the workers were called in to Haukeland Hospital in Bergen for a medical check-up, and many of the workers were diagnosed with silicosis, but nothing was done.

Snow avalanches and rockslides

There were several instances of avalanches and rockslides down the steep mountainsides in the valley of Flåmsdalen during the construction period. In the autumn of 1924, there was a major rockslide at Høga which blocked the railway line and the rural road. The slide was quickly cleared of rocks, but because of loose rocks, it was decided to build a tunnel past the slide-exposed area. However, this solution turned out to be too expensive. Instead the line was moved further out from the mountainside and a deep ditch was dug in towards the mountainside in order to "catch" any rocks that might fall from above. The road was moved to the other side of the valley with two new bridges.

In 1925, a snow avalanche hit Store Reppa, so the entrance to the planned tunnel was blocked. In April the same year, a big rockslide of 1000 cubic metres fell above Berekvam without destroying the railway line. In 1928, there were snow avalanches at Nåli, Blomheller tunnel and at Lille Reppa. Huge blocks of rock up to six cubic metres at Lille Reppa smashed the road bridge. The other avalanches did not have any serious consequences.

The transport men

Many of those who carried out transport work for the railway also drove tourists. They transported tourists in daytime and at night they carried out transport of materials. This meant hard work for man and horse. They were actually not allowed to make more than three tours a day. For some time there was even a "horse police" who checked whether the horses were properly shod and were well taken care of. The transport to the construction sites could consist of food provisions, equipment, tools and other materials. Down from Myrdal they had to use packsaddles on the horses down the steep scree. The horses were also used to pull rocks and soil along the planned railway track.

Temporary opening

The Flåm Railway faced many difficulties. Many people wanted to stop the whole construction project, but neither natural disasters nor decreasing allocations could stop the progress, even if the work went slowly. In 1936, the work was started to lay the rail. The railway was temporarily opened on 1 August 1940 for goods traffic, after much pressure from the Germans. The reason was the need to transport materials to the aluminium plant that was being built at Årdal. On 10 February 1941, the railway line was opened for passenger traffic as well. From Myrdal down to Flåm the train took 65 minutes, whereas the uphill journey took 80 minutes. Today the driving time is 5o minutes either way.