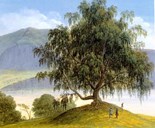

The birch tree and the mound no longer exist

The Slinde birch was located on a farm at ¿Indre Slinde", on a mound called Hydneshaugen, a place where several property borders met. One interpretation of the word ¿hydne" may be a corner, another explains it with the name of a person - Hydne - thus the whole word may mean Hydne¿s hill (or mound). The mound no longer exists, and the landscape where it was located, a short distance west of ¿Slindesenteret", has been changed by the building of a road and a house.

In 1996, some people brought up the idea to mark the place so that travellers could get a chance to stop where Fearnley and the other painters from the National Romanticism period had painted this well-known birch. Nothing came out of this idea, apart from the fact that a completely unofficial birch tree was planted there on the occasion of a family reunion. The birch has later been cut down. It was planted at a highly unsuitable place for a tree to grow big.

"The protected tree"

The giant birch tree at Hydneshaugen blew down in a storm in the autumn of 1874. The elegant tree would most likely have been forgotten today, if it had not been for the painters who came there in the early 19th century to make sketches, later turned into magnificent works of art. In addition, the writer Johan Sebastian Welhaven wrote a poem about the birch, and the museum man, (better known as President of the Eidsvoll Assembly in 1814), Wilhelm Frimann Koren Christie, wrote a lengthy article entitled ¿Of a strange birch tree on the farm Slinde in Sogn" in the Bergen Museum periodical ¿Urda I".

Welhaven¿s poem - containing seven stanzas - is entitled "Det fredede Træ" (The protected tree), and the first stanza goes like this (freely translated):

By the Sognefjord on the Slinde farm,

We find the proudest birch tree;

On the Hydnes mound, on its gigantic leg,

It stretches its massive branches,

And is highly honoured,

And can carry its age up to the clouds.

Size and shape

Amund Helland refers to the Slinde birch in his book "Topografisk-statistisk beskrivelse over Nordre Bergenhus Amt" which was published in 1901. He writes that in 1861 the tree had the following measures: a) the short trunk at the ground level had a circumference of 5.6 metres (some 18 feet), that is, more than two grown men could encircle, b) the total height was 18.8 metres (about 53 feet), and c) the canopy had a diameter of 21.6 metres (about 73 feet).

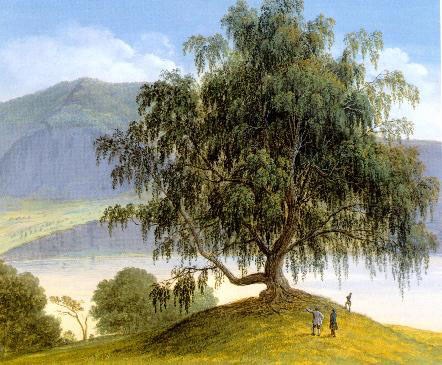

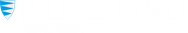

The paintings and sketches by the artists are not photographically correct, and therefore do not show the "same" tree from one picture to another, but they all show a heavily branched tree from the very ground and up. This also applies for the three illustrations to this article. Fearnley¿s painting shows a short basic trunk which then branches out. Dahl¿s painting gives the impression of a main trunk with two side trunks from the root, whereas his drawing looks more like a tree with four trunks from the very root.

Christie¿s visit in 1827

Christie was on a visit to Slinde in 1827, and in his article on "the strange tree" a few years later, we can sum up his impressions of what he saw and heard.

The birch stood an a mound called "Hydneshaugen" on the farm "Indre Slinde" where there were two tenant farmers. The mound consisted of big rocks and was located not far from the fence of the outlying field. People said that the mound represented a border line where a number of properties met. From what people said, he understood that the birch had been looked upon as ¿sacred" from time immemorial, and that it was still looked upon as such. They assured him that no sharp objects such as knife or axe had ever been used on the tree, meaning that no part of the tree - trunk, branches or foliage had ever been removed. He also heard that from days of old it was customary to pour a pot of good beer on its root at Christmastime, but that this custom was no longer in use.

Christie wondered if there were any legends or myths linked to the mound or birch. An old farmer told him that according to an old legend, twelve copper kettles, one inside the other, as well as a money chest were said to have been buried there, and that these treasures were guarded by a white snake. The man added that the people of the farm had held the belief, and still did, that disaster would strike themselves or their cattle if anybody did any damage to the tree.

Remnants of a pre-Christian cult?

In his article Christie attempts to find explanations for people¿s relationship to the tree and the traditions linked to it. In his opinion, the most profound reason must be sought in a pre-Christian cult, in customs and practice found among the Norse people before Christianity was introduced. He refers to examples that beliefs and customs linked to ancient cults could live on centuries after the introduction of Christianity, and that the tree in many places represented ancestral worship and religious cult.

Information in Per Fett¿s register

What happened to the Hydneshaugen mound? Where treasures hidden there? In Per Fett¿s register of ancient monuments which was published in booklets for each municipality in the years after 1945, we can read that the mound measured 19 metres (about 63 feet) in diameter, its height was four metres (some 13 feet), and was built with a 30-centimetre- thick (one foot) layer of soil on top of a core of rocks. No copper kettles or money chests were ever found, but instead two stone-lined "coffins" with a few objects, all dated to the early Iron Age.

Fett refers to the mound as King Hydne¿s hill, or the King¿s hill. This is an indication that folk tradition has a different explanation of the name from Christie¿s ¿corner theory". The expression "The leg of the giant" in Welhaven¿s poem may also indicate that the poet has been aware of a local understanding that it must have been a high-ranking person who was buried in the mound.

Not excavated by archaeologists

Fett¿s find information is based on a conversation with Ivar Venjahola who in June, 1893 came to Bergen with the grave objects found in the mound. It was people from Slinde who in the winter of 19892/93 had removed the mound. 3000 loads of rock had been removed, and, in the course of the work, they had found two stone-lined ¿coffins" and a few ancient objects.